Robert H. Shelton, Vice President H2C Safety Pipe Inc., and Murtaza Fatakdawala, Engineer at H2 Clipper and H2C Safety Pipe Inc., explain how historical insights from natural gas pipelines and underground storage tanks can help inform hydrogen infrastructure in the USA.

In the 1920s, America’s energy landscape was heavily dominated by coal. Although natural gas was also present, it played a minimal role in America’s energy mix, primarily being utilised at the time for residential heating and cooking. Although the first significant natural gas pipeline was constructed in 1891, early pipelines were generally less than 100 miles in length through the early 1930s, significantly limiting the growth of the industry. Due to transmission and distribution constraints, natural gas was used only in communities that happened to be located close to where it was produced.

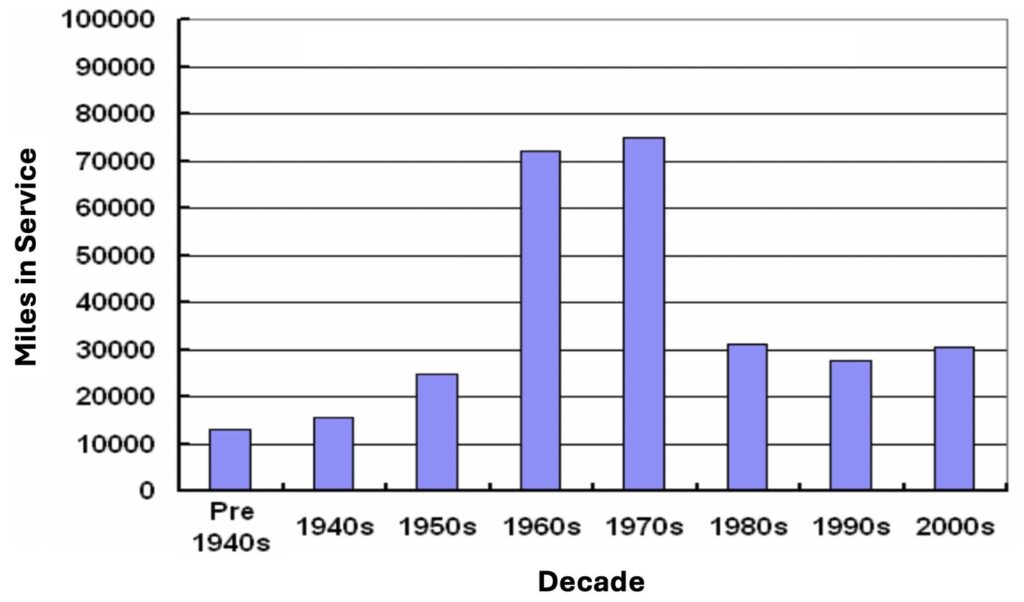

Following World War II, the demand for natural gas surged, prompted in part by an expansive build-out of the pipeline network, and the opportunities opened by low-cost, reliable transmission and distribution. Whereas in 1940 there were less than 15 000 miles of natural gas transmission pipelines, by the end of the 1960s, the US had established approximately 250 000 miles of gas transmission pipelines and 600 000 miles of distribution lines.1 This network has continued to grow, and today the natural gas network in the United States includes over 300 000 miles of transmission pipelines and well over 2 million miles of distribution and service lines. This vast network enables natural gas to be a cornerstone of the nation’s energy mix, supporting a wide range of needs from industrial processes to residential heating and cooking.

Historically, natural gas leakage from this vast network of pipelines has been somewhat dismissively accepted by the industry as an inevitable cost of doing business. Some industry experts attribute the reason for this being that because most oil and gas operators oversee many thousands of miles of pipelines, manual checks are – as one observer characterises – “impractical at best and expensive, ineffectual time sinks at worst.”2

Other experts note that because lost gas has historically been treated as a cost of doing business that can be included in a utility’s rate basis, regulated gas transmission companies have little incentive to invest capital resources to abate such losses. Even among regulators, until the last few years, as worldwide concerns about methane emissions have increased, the prevailing view was that methane – the primary component of natural gas – did not pose an immediate environmental risk since, unlike liquid hydrocarbons, it didn’t pollute groundwater or surface waters. Accordingly, its leakage from natural gas lines was seen as a tolerable loss, economically insignificant enough not to impact the industry’s bottom line substantially.

Underground storage tanks

The history of safety and environmental regulation surrounding underground storage tanks (USTs) is considerably different. In 1970, the oversight landscape began to change with the establishment of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Roughly a decade after the EPA was formed under President Nixon in the 1980s, televised reports of major gasoline leaks under some filling stations raised broad public concerns about specific challenges posed by USTs.3 These tanks, especially those containing petroleum and hazardous substances, were identified as significant sources of environmental contamination, often leaking as they aged and, in turn, contaminating crucial groundwater supplies.

Figure 1. Miles of natural gas transmission pipeline added, by decade, in the USA. (Source: INGAA ‘Integrity characteristics of vintage pipelines’, October 2004, Figure 1, p.5)

In response, the EPA implemented a more robust regulatory framework under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). In 1984, Congress added Subtitle I to the Solid Waste Disposal Act to protect the public from underground storage tank petroleum releases. This legislation mandated significant upgrades of USTs and any underground pipes connecting to them and banned the installation of new, unprotected steel tanks and piping.

By 1998, the regulations mandated that all USTs had to be upgraded or replaced, or such tanks were required to be permanently decommissioned. To prevent leaks, the stringent measures mandated that owners and operators of petroleum USTs employ double-wall containment. In addition, to know when a problem was emerging, the regulations required monitoring systems to detect the release of product into the interstitial space between the inside wall of the pipe or tank, and the outside secondary containment wall.

However, natural gas pipelines were specifically exempted from these stringent measures. 4

If we fast forward to today, what has transpired because of these decisions is significant. UST leakage is no longer a problem, and yet the EPA estimates that current leakage rates across the natural gas supply chain are 2 – 3%, and studies conducted by independent groups report considerably higher levels.5 Detailed studies performed by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) show that actual methane leakage could be up to eight times greater than the EPA estimates.6

Looking forward to hydrogen pipelines

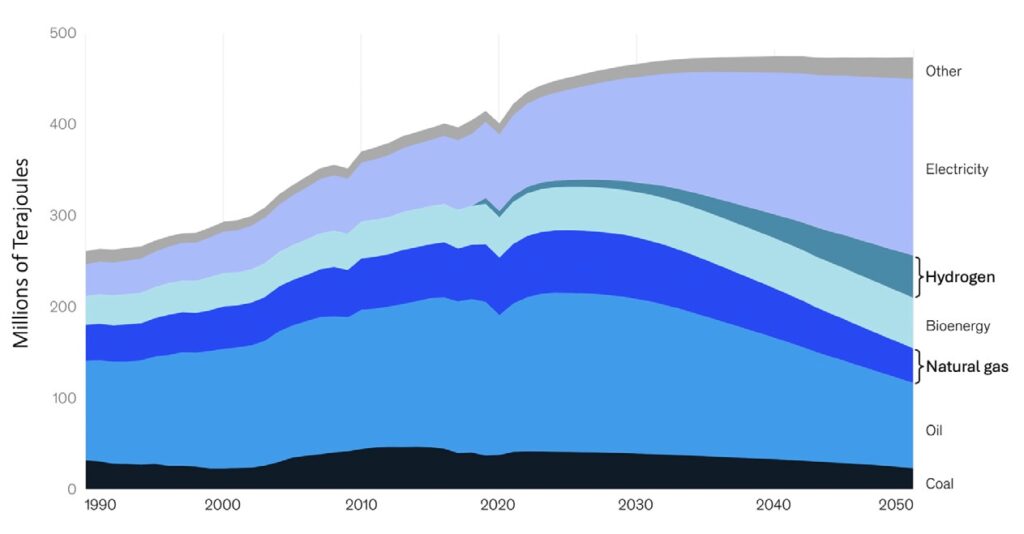

McKinsey & Company forecasts that by 2050, hydrogen will eclipse natural gas in the energy mix as nations push to meet ambitious decarbonisation targets to address climate change. Yet, like the practical constraints on the natural gas industry a century ago, the absence of a widespread transmission network to provide low-cost and reliable distribution severely limits the hydrogen industry’s ability to grow. Currently, there are just 2000 miles of hydrogen pipelines worldwide, with a little over 1600 miles in the US, primarily serving refineries along the Gulf Coast.

Still, just as World War II provided a catalyst for dramatic increases in natural gas use, climate change and massive government incentives are poised to press hydrogen into widespread service today. The US Department of Energy’s ‘Hydrogen Shot’ goal of cutting the cost of clean hydrogen production to US$1/kg and the final dispensed cost of hydrogen to less than US$7/kg by 2031 would put the cost of hydrogen on parity with fossil fuel products.

Once this is the case – once the price of hydrogen from renewable sources drops to the level where it is at or below the cost of fossil fuel products – natural economic forces are primed to propel its growth. As the US$6/kg difference between the cost of production and the final dispensed cost suggests, the efficiency of hydrogen transport and distribution will play a major role in how rapidly and widespread the industry grows.

In this regard, the history of natural gas is instructive. If the transmission and distribution infrastructure develops for hydrogen to support its widespread use, the hydrogen industry will grow exponentially over the coming decades just as did natural gas between 1940 and the end of the 1960s.

The projected scale of hydrogen use and its pivotal role in achieving climate goals necessitate a thoughtful approach to the development of this emerging

transmission and distribution infrastructure. Hydrogen carries significant safety risks due to its flammability and propensity for leakage, which is substantially greater than natural gas due to hydrogen’s substantially smaller molecular size. Moreover, while hydrogen is not a greenhouse gas, it has been shown that its release into the atmosphere may be harmful because, although it does not cause a warming effect on its own, hydrogen interacts with airborne molecules called hydroxyl radicals to prolong the lifetime of atmospheric methane as well as increase the production of ozone, another greenhouse gas.

Recently, a study by climate scientists from four countries and across six institutions concluded that the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of atmospheric hydrogen is between 8.8 and 14.4 times that of CO2 over 100 years.7 These and other studies by groups such as EDF demonstrate why serious attention must be given to reducing the leakage of hydrogen to get the full climate benefits from its usage. Here too, America’s experience with USTs and natural gas pipelines can be instructive.

Learning from past mistakes and successes

While scientists today can debate the degree to which these concerns about hydrogen as an indirect greenhouse are correct, one thing seems certain. If policymakers in the past had today’s understanding of environmental impacts, they certainly would have mandated more robust protections for natural gas pipelines, akin to those required both under RCRA and corresponding state regulations for USTs and underground petroleum pipelines.

It is estimated today that the cost of remediating the leakage of subterranean methane pipelines is US$1 million/mile in an unpopulated city and US$8 million/mile in a city like Boston. 8 At such high costs, in many ways, it’s too late for natural gas and we are condemned to play ‘whack-a-mole’ as specific leaks are discovered that are simply too large to ignore.

Figure 2. Final energy consumption per fuel in the USA. (Source: McKinsey & Company, ‘Global Energy Perspective 2022’, April 2022.)

However, the level of hydrogen infrastructure buildout today is where the natural gas industry stood in the 1920s, and thus there’s a real opportunity to be proactive.

Environmental groups such as the EDF and the Sierra Club are right to demand that we should not repeat past mistakes as we plan for the extensive infrastructure necessary for hydrogen. In short, the public should demand, and regulators should require, that hydrogen pipelines follow the successful case of USTs.

Today, we possess the foresight that was absent in the past. We better understand the broad implications of our choices for future generations and the environment. By instituting rigorous safety standards now, such as requiring secondary containment around all hydrogen pipelines and storage tanks and mandating active leak monitoring and mitigation systems so that issues are addressed well before they become problems, we can establish a global standard for safe, sustainable energy distribution networks that are essential for our transition to a low-carbon future.

Such solutions are at hand. We simply need to muster the resolve to employ them.

References

1. Interstate Natural Gas Association of America “Integrity Characteristics of Vintage Pipelines”, October 2004. https://bit.ly/4blVa8L

2. NAPLES, M., “Will 2024 be the year the world wakes up to methane emissions?” MaintWorld, 3 August 2024. https://bit.ly/4amRNwS

3. United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Milestones in the Underground Storage Tank Program’s History.” https://bit.ly/4aipWy3

4. Code of Federal Regulations, 40 CFR 280.12. https://bit.ly/3yjAm34 (subpart 4 exempts all natural gas pipelines from the definition of a UST).

5. STORROW, B., “Methane Leaks Erase Some of the Climate Benefits of Natural Gas,” Scientific American, 5 May 2020. https://bit.ly/4adR0yo

6. MCVAY, R., “Methane emissions from U.S. gas pipeline leaks,” Environmental Defense Fund, August 2023. https://bit.ly/4dH64rs

7. PARKES, R., “Hydrogen is a more potent greenhouse gas than previously reported, new study reveals,” Hydrogen Insight, 7 June 2023. https://bit.ly/3QMtUbn (22.2 to 52.5 times higher GWP over 20 years)

8. MIT Climate, “How much does natural gas contribute to climate change through CO2 emissions when the fuel is burned, and how much through methane leaks?” Climate Portal, July 17, 2023. https://bit.ly/3yfJwOe